Is SNAP (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as food stamps) doing enough to protect the health of its 42 million recipients?

Food insecurity is a social determinant of health, so programs such as SNAP which alleviate food insecurity through providing funds for food purchases, do indeed improve the health of their recipients. A 2017 study out of Boston found that SNAP recipients spend $1,400 less on health care than individuals at the same income level. The assumption is that reduced health care expenditures are linked to better health.

But could SNAP’s nutritional impact be improved? Low-income populations are at greater risk of diabetes (70%) and hypertension (19%) than the highest income populations in the US.

Two entities on opposite ends of the political spectrum think so. Let’s consider the merits of their proposals.

The Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine’s “Healthy Staples” proposal seeks to limit SNAP purchases to only healthful products, such as grains, vegetables, fruits, beans, and vitamins. It looks to the Women, Infants and Children (WIC) program as a model. WIC provides vouchers for high-protein items, infant formula, produce, and healthy cereals as a nutrition supplement for vulnerable women and kids. Laudable in its goals of decreasing consumption of unhealthy foods, this proposal falls short on a number of different levels, including the following:

- First, it limits protein sources to legumes only. Most nutritionists agree that a healthy diet can include eggs, low fat dairy, fish, and lean meats. The Mediterranean diet, which this proposal emulates, does include many of these foods. This proposal would require unrealistic changes to the dietary patterns of most SNAP recipients, or even most Americans.

- The proposal assumes that the SNAP population has more time available to prepare healthy meals than many do. Many SNAP recipients work long hours at multiple jobs, are elderly, disabled, or single parents, or have multiple stressors in their lives which impede them from spending hours cooking every day.

- The proposal seeks to re-cast SNAP as a supplemental dietary program, as stated in its name. That may have been Congress’ intention, but it does contradict the reality that for many people SNAP represents the vast majority, if not all, of their food budget. To call it a supplement only works when recipients have additional income with which to purchase food. The proposal does not explain where that additional income will come from.

Maine

On the conservative end of the political spectrum, Maine requested for a second time in February 2017 a waiver of USDA rules to allow them to exclude candy and sugar sweetened beverages from SNAP. Many anti-hunger advocates had considered this to be a punitive request, given the well-documented antipathy of Governor Le Page for federal nutrition programs. For example, he had threatened to terminate Maine’s participation in SNAP when the Obama Administration denied a similar waiver in 2016.

Last month, USDA denied this waiver request as it has done for similar requests from the states of New York, Minnesota, and Illinois. The Department expressed concerns about the proposal’s administrative costs, burden on small retailers, as well as the lack of clear and meaningful health outcomes that would come from such a restriction.

Many of these concerns echo those of the food industry. The National Association of Convenience Stores penned a letter to USDA last fall opposing the waiver, stating, “Food retailers would become the frontlines of enforcement, facing added costs and loss of interoperability that would undoubtedly increase error rates.”

These technical concerns echo those of the previous administration (which also denied waiver requests because they felt it would send the wrong message about the ability of poor persons to make healthy choices).

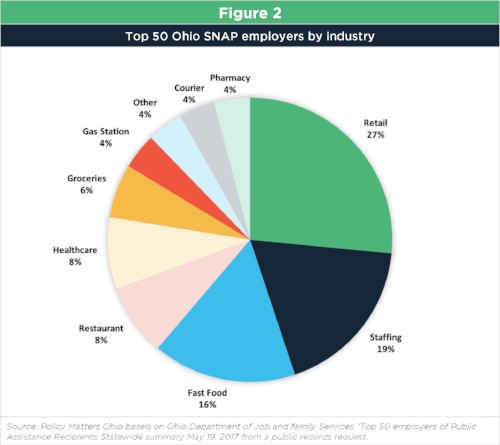

Nonetheless, USDA Secretary Sonny Perdue also noted, “We don't want to be in the business of picking winners and losers among food products in the marketplace, or in passing judgment about the relative benefits of individual food products." In doing so, he brought to light the fact that USDA has a long-standing role to protect and promote America’s agri-food industry. It sees SNAP as an integral part of stabilizing and supporting the retailing and food production industries. Just as former USDA Secretary Vilsack would famously claim conventional agriculture and organics to be his two sons, and that he would not be able to make a choice between them, Secretary Perdue sees USDA as creating a value-neutral big tent for the food industry.

His statement communicates the following message “Come on in. There’s room enough for y’all to make billions off SNAP. No judgment here.”

Analysis

It seems likely that USDA will continue to feel some pressure to change the nutritional profile of SNAP. The Bi-Partisan Policy Center will be issuing its recommendations in this matter in March, which most likely will include suggestions to exclude soda. Maine promises to come back with another waiver request, and other states will likely follow suit. For example, the Delaware legislature is currently considering a bill that would move forward a waiver request. And it has long been rumored that the House Agriculture Committee may include provisions that either mandate or incentivize such changes in its version of the 2018 Farm Bill.

Despite this pressure, one anonymous West Coast anti-hunger advocate sees a low likelihood that USDA will issue a soda-exclusion waiver. She believes that USDA’s focus on holding down program costs would preclude them from making the program more complicated to administer. She also notes that most anti-hunger groups would be opposed to such a waiver under the current administration, as it would likely be punitive in nature, given the Trump administration’s antipathy toward the poor. The health impacts of increased poverty from potential SNAP cutbacks, to her, outweigh the risks of continued access to harmful foods and diets from the current program.

Given these factors, perhaps the only way to make SNAP a true nutrition program is to move it under the purview of the Department of Health and Human Services. This was attempted and failed in the 1970s, due to opposition from anti-hunger groups, who feared that doing so would break the links to the agriculture industry and result in funding cutbacks. The chance of doing so in the near future is virtually nil. To many anti-hunger groups, SNAP remains one of the last and most important anti-poverty programs in existence. They could only support it becoming a true nutrition program if Congress were to create and fund another major national welfare program, such as universal basic income. That seems a non-starter based on the current composition of the federal government.

So it appears that, for good or for bad, barring effective leadership in Congress, product exclusions in SNAP are stalemated until 2021 or beyond. Incentives for healthy food may be another matter and subject for a future article.

.